Mornington Crescent

Mornington Crescent was built as a sweep of houses with gardens and tennis courts in front. Tenants paid a garden tax each year for the right to use the gardens, which were railed off and maintained as a private space for key holders only. At the beginning of the twentieth century the area, with large rooms suitable for studios, became popular with artists. Sickert lived at No 6, while Gore had lodgings in the Crescent and Gilman, another of the Camden Town Group, lived nearby in Cumberland Market.

|

|||

| 1864 | Whole Map | Full Map | Full Size Map in New Window |

| 1896 | Whole Map | Full Map | Full Size Map in New Window |

| 1915 | Whole Map | Full Map | Full Size Map in New Window |

++Insert piece about artists moving in.

When Walter Sickert came back to London in 1905, after seven years abroad, mostly based in Dieppe, he became the doyen of a group of young painters. ‘They took their inspiration from the dingy streets and lodgings houses of Camden Town’.1 Indeed one of Sickert’s most famous paintings is ‘The Camden Town Murder’, a sordid, but pitiful affair. It was not the only one. Ford Madox Ford tells the story of ‘The Euston Square Murder’2. Borschitzky, his violin teacher, ‘came home late at night and found his landlady murdered in the kitchen. Being nearly blind he fell over the body, got himself covered in blood and as a foreigner and a musician was at once arrested by the police. ’He was acquitted but the publicity caused Euston Square to be renamed as Endsleigh Gardens, a name we shall hear again later.

The Camden Town artists painted the streets, the cafes, the gardens behind their lodgings, the public parks and the music halls. The Bedford Music Hall, in its worn Victorian red and gilt, was a favourite subject, especially of Sickert. Over the years, Sickert ran several painting schools in the area, which drew in other artists. There were links with the Bloomsbury Group through Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, who both painted with them. The artists varied in their subjects and palettes, but they exhibited together and became a very influential group. Mornington Crescent Gardens were the subject of several paintings and drawings.

Mornington Crescent Gardens, 1913-14 by Gilman, 1913-14 3

When first laying out their estates in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, ground landlords had realised that houses with gardens behind and private squares in front, would be more attractive than dense rows of terraced streets. To attract a ‘good quality’ of tenant and to continue to hold them, landlords laid down the maximum number of houses to be built per acre, the value of the properties to be erected, insisted on householders repainting the properties at regular intervals and made annual maintenance inspections. In addition many landlords laid out private gardens in squares, crescents or circles to give fresh air and green spaces near the houses. Householders paid a Garden Tax and were given a key to the private, railed garden in front of their houses. Purchasers valued the healthy living conditions, the open sky and the attractive trees. By the time that house building slowed down at the start of the First World War, there were said to be 40,000 ‘squares’ in Greater London, of all shapes and sizes.

As Camden Town went down, houses were let in floors and rooms, often with cooking facilities on landings. Tenants and sub-tenants moved in and out frequently, making the garden tax difficult to collect. The gardens were no longer maintained, tennis courts fell into disrepair and the Crescent became a wasteland. One man remembers as a young boy, walking across this rough ground from his home in Delancey Street to the Tolmer Cinema, at the corner of Euston Road and Hampstead Road, where the Tolmer Estate now stands, to see Tom Mix or Rin Tin Tin for a penny. Sometimes a small fair was held in the Gardens, or a travelling circus appeared. It became a village green, untended but friendly. After some years the site was boarded all round with poster hoardings. Slowly the news filtered out that the land, long regarded as public open space, had been bought by some unknown developer. This caused a great public outcry and linked Mornington Crescent Gardens to the far wider campaign for public open spaces.

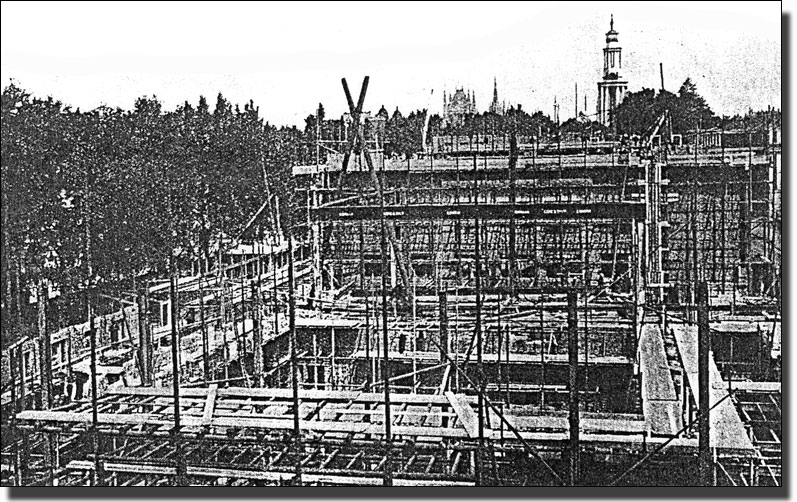

Building operations at Endsleigh Gardens, Euston Road, c. 1928.

St Pancras Church can be seen in the distance.4

Mornington Crescent was only one of the many squares and crescents under threat by developers in the 1920s. Another was Endsleigh Gardens, opposite Euston Station. It had been an open space full of trees, but was now lost to the public. This is the block which now contains the Friends’ Meeting House. Coram Fields and many other green lungs were under similar threat.

In April 1928, ‘New Health’, a periodical which fought for open spaces in cities and the health which they could bring, was up in arms about the planned loss of Mornington Crescent Gardens. Fresh air was the sole known cure for killer diseases such as tuberculosis. Streptomycin, which emptied our TB hospitals in the early sixties, was thirty years away. New Health contrasted the trees and open space with the effect of a new factory on the area.

Captions from ‘New Health’

| "Look at this picture which shows the gardens at Mornington Crescent some years ago, when trees and shrubs and grass brightened the surroundings of this North London district." |

| "And on this, after the builder has fallen upon the ground and work has commenced for the erection of a great factory." |

Pictures of Mornington Crescent, with hoardings and during development

The New Health article went on to demand that all new factory building should be outside London as there was plenty of room in the countryside and London needed its open spaces to give the population fresh air and health. It was partly this thinking which would begin to empty Camden Town of manufacture thirty years later, well after Mornington Crescent Gardens had been built over and, incidentally, just when Streptomycin was beginning to solve the Tuberculosis problem.

The Carreras 'Black Cat' Factory

In 1927, when the factory was being designed, interest in Egyptian history was widespread. Lord Carnarvon had discovered the tomb of Tutankhamen a few years earlier and a number of 'Egyptian' buildings were being erected at this time, including the Hoover factory on the A40 into London and a cinema in Essex Road. The association with Black Cat cigarettes, then a popular brand, related to an earlier period in the Company history. A Spanish nobleman by the name of Carreras, banished from his country, set up in London's Wardour Street and began trading as a tobacconist/herbalist. He had a black cat which, on sunny days, sat in the window of his shop. Londoners wishing to buy tobacco used to ask cab drivers to take them to the tobacconist's shop in Wardour Street with the black cat in the window, because the name Carreras was difficult to pronounce. Thus the Black Cat name became famous. The combination of the Egyptian theme and the Black Cat, led to the Egyptian Cat Goddess, Bast and helped decide the system of decoration. Local people still call the building the Black Cat Factory.

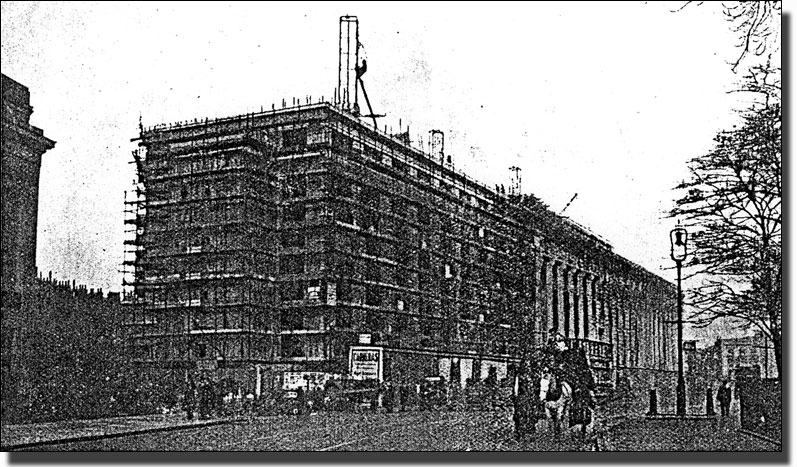

The new factory was to be enormous - the largest reinforced-concrete factory in the country. Five floors would completely fill the gardens. Not an inch was to be left and everything green would disappear.

Five deep light wells were to penetrate the building, bringing light and air to the interior, while the top floor was to have north-facing lights, so that heat would not build up in strong sunshine.

The huge factory built over the valuable garden space of Mornington Crescent,

Camden Town, N. London.

Note, on left, the original houses overshadowed by its bulk

Pictures of the building under construction show three tall steel towers, the forerunners of our modern tower cranes, and huge walls of wooden shuttering for the concrete. Trams and buses with outside staircases pass along Hampstead Road. When built, the whole of the exterior (except the coloured parts) were rendered in white cement and sand to give a warm stone-coloured finish. The brilliant Egyptian decorations were produced by mixing ground glass with cement and grinding off. Thus the colours were permanent and, when dirty, could be washed.

|

||

| Whole Plan | Full Plan | Full Size Plan in New Window |

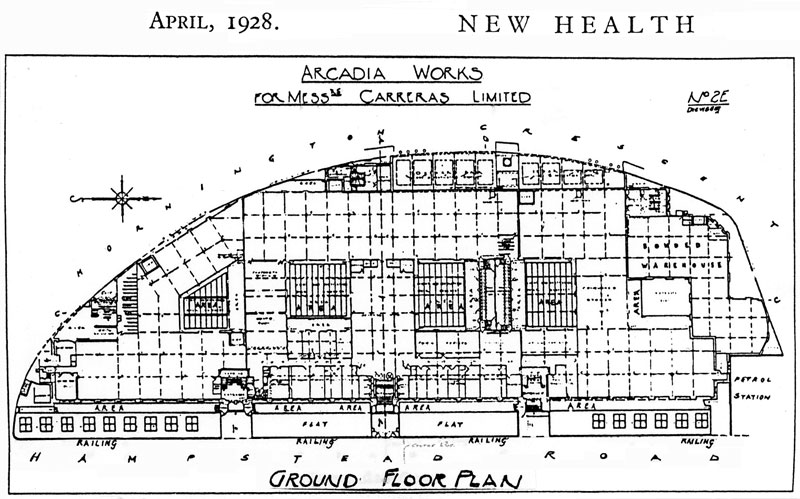

New Factory for Messrs, Carreras Ltd., Hampstead Road NW1

Architects, M.E. and O.H. Collins .Contractors, Sir Robert Mc Alpine & Sons.

The First Reactions

In 1928, the reviewer in 'Building' was very doubtful about the design of the factory. The idea of dressing up a modern factory as an Egyptian temple was disturbing, but the mass of the building, its form and general composition, were unexpectedly beautiful. He closed his eyes to the decoration and looked at the building beneath. The 'sense of beauty' given by the gentle inward slope of the walls, typical of Egyptian building, is particularly satisfying.

Of course, the inside walls are vertical, as with Egyptian mud-brick building, but from the outside they slope inwards, gradually tapering in thickness to the top. An inward slope, or batter, is very rare in reinforced-concrete work, but when we see the factory today, with the Egyptian fancy dress gone, we see the building as the reviewer in Building imagined it and so can judge it on architectural merits alone. The reviewer too was very impressed with the beauty of the vast concrete interiors, 'unplastered and straight from the shuttering (just stoned down and white-washed over)’. Although he did not know it, this as an early example of New Brutalism, but the coloured decoration protected it from that name at the time.

The new Carreras factory about 1929, in all its Egyptian finery

The History of the Rothman Tobacco Firm

The modern firm of Rothman had been founded by Bernhard Baron, who had come to England from Kiev, via the United States. There is an old news film about the opening of the Carreras factory which seems to be from another age. It records the opening ceremony and shows Baron being greeted by a vast crowd. Apparently almost all the 3,000 workers, mostly women, are waving at him. Other pictures show them crowding into the main doors on a working day in such numbers that the scene looks like Wembley five minutes before the kick off.

The original silver nitrate film has been transferred to video, silent and jerky. Short panels of text say:-

|

|

|

|

|

Our modern reaction to the film is very different from the impression it must have made on its first audiences, because we have the advantage of hindsight. In the nineteen-thirties we regarded cigarettes as a source of harmless pleasure. We watched Hollywood films and copied the way the film stars lit their cigarettes. Whenever an actor on the stage needed some 'business' to cover a pause, or hoped to take the audiences' mind off the quality of the dialogue, he flourished a cigarette case. Every theatre programme used to carry the acknowledgement, 'Cigarettes by Abdulla', because Abdulla gave free cigarettes for use on the stage.

Thus, when Carreras moved to Camden Town here was pleasure and relief at the prospect of employment. Hundreds of people would have the chance to work in a modern factory which had the latest air conditioning. The film opens with pictures of the park at Mornington Crescent, full of small trees, almost as Ginner and other artists in the Camden Town Group had drawn it before the First World War.

It then traces the making of cigarettes in their millions. Women open bales of tobacco leaves and rapidly strip out the hard central vein, with the dust of broken tobacco leaves rising in their faces for eight hours a day. This was passive smoking, but nobody knew. Smoking cigarettes was glamorous, not stupid. Reading the laudatory film captions about the new factory, we are shocked. Not until the computer death figures began to appear nearly forty years later, did we realise the danger of cigarette smoking, while the risk to passive smokers like these took us even longer to recognise. Watching the film today we look on now helpless, unable to warn them of their likely fate.

All methods of advertising were used to keep up sales. 'Club brand’, made at the Mornington Crescent ‘Arcadia Works’, was the first to give coupons which could be exchanged for goods of all type. In that realistic 1930 world, some of the most popular 'prizes' were boots and shoes. Smokers came to the main entrance, collected their footwear and changed into the new ones at once. So many left their old boots and shoes on the doorstep that one boy had the special job of collecting them every few hours to keep the place tidy. Mr King remembers going up the splendid 'marble' staircase and handing in the coupons. His brother too got his first overcoat with coupons.

Every street in Camden Town provided workers and, since it was the policy to employ families wherever possible, whole households worked there together. This made for a more stable workforce and created a subtle type of discipline. If a younger member of the family was not behaving well, a word to an older relation often settled the matter. This policy of employing families was pursued by Gilbey's and other local factories until the 1960s, when the patterns of employment and the early breaking up of families into separate households, often living far apart, made it impracticable.

On Christmas Eve the family party often started in the factory. Any musicians were encouraged to bring their instruments. At about 3 o'clock, the band started at the top floor and formed a conga chain, dancing through the factory, floor by floor, until it emerged at the main entrance as an excited throng and held up the traffic in the Hampstead Road.

Camouflaging the Factory

In 1939 the factory was camouflaged in broad patches, which appeared to make it even more gaudy and conspicuous than ever, but it looked different from the air. After the War the camouflage was removed and the Egyptian decorations were restored. However, the proud boast of 'outlasting centuries' seemed unlikely to come about, for in 1958-60 the Carreras factory was relocated to Basildon, Essex. Some workers went with the firm to the new town, and its new houses, while others had to find what other London work they could. Rothman’s were to move again from Basildon to Aylesbury, but that factory too is now closed. One of the famous cats was in store and the other is at the Rothman factory in Jamaica.

Modernising the building

When Rothmans had left, the factory stood idle. The building was refurbished. Windows were replaced. All the glass-decorated pilasters were built in as square columns; the winged orbs of the Rah the sun god above the entrance were removed; the building was given a plain colour wash, and the factory could be seen at last as a modern building. With the Egyptian decorations removed, many ‘Egyptian ‘ features remained. There were still the ‘battered’ walls, sloping in gently towards the top; the cavetto mouldings at the roof; the Egyptian shape of the building, the tall, narrow window openings, used by the Egyptians; a row of circular patches along the front which were part of the original Carreras decoration; and the iron railings with their hieroglyphic motifs. Despite these traces of the past, it became the modern building with its simple inwards ‘batter’, first envisaged by the critic in ‘Building’, in September 1928

.

The factory was renamed ‘Greater London House’ and the Thomson Travel Company has been located there for many years.

The logo of

Thomson Travel

The 1997 Changes

In March 1997 the building changed hands. The new Taiwan-based owners submitted plans to restore the building, replace all windows to match the 1920s originals and reintroduce the 12 foot high black cats at the entrance. The original columns, with their glass decorations have been too damaged by building them over into square columns for the originals to be restored, but new ones would be built over the top of the old and painted to the original colours. The huge black cats would be replaced, and an ‘Egyptian’ building was to become a post-modernist Egyptian one.

It is a very well designed building, with high ceilings and large open floors, ideal for a computer-run world. Modern offices bear little relation to the traditional office of high desks and coal fires. Dickens, who went to school just by Mornington Crescent, and Bob Cratchet, his clerk in The Christmas Carol, are both long dead. Instead of ledgers and dusty files stored in attics and tied with tape, each person has a computer. This can be plugged into any socket, or worked by batteries. Today many office workers are ‘nomads’, travelling around from site to site, customer to customer, and have no need for a permanent space. They can use any convenient empty desk and call up their files on their lap-tops. They have a cubic metre of drawer space in a steel filing cabinet, a lap-top computer and a car which doubles as an office.

Thus many modern offices need only a reception area; rooms for meetings; some small office cubicles where one can work quietly for an hour; a place where people can meet casually; and a kettle for making tea. Architects will need a drawing board and a computer, but even these may sometimes be shared. Solicitors still require a permanent room where the door can be shut and confidential matters discussed in private. Most work however is not very secret. It is routine and can be conducted in open offices.

This is the new pattern for Greater London House. A number of flexible office spaces capable of being used in many different ways, with good communications, minimal overheads and a newly refurbished Mornington Crescent Station outside.5

Footnote